Q: Should I plant carnivorous plants in habitats they don't live in already?

A: The official stance of the International Carnivorous Plant Society

is that in most cases the planting of exotic (also known as "non-native")

species is not appropriate. (The word "exotic" is used in its

original sense, meaning "something originating from somewhere else.")

The Nature Conservancy considers that exotic, and especially invasive,

species are a top threat to conservation. They have good reason to be concerned,

for introduced species are the cause of more species extinction than

anything except for habitat destruction! (You may want to look at the

FAQ entry about exotic species)

Dionaea in California

Carnivorous plant enthusiasts love their plants, love seeing them in the wild, and some love

the convenience and thrill of having them grow nearby (instead of across the country or on another continent).

I can understand---I have seen Drosophyllum in the wild, but it was hard getting all the way

to Portugal and Spain. On the other hand, the mere mention of non-native plantings of carnivorous plants will

make other carnivorous plant growers very mad. This is a topic sure to cause arguments on-line, or face to face!

My own perspective, of course, is that non-native plantings are wrong.

To analyze the situation with delicacy, I think I can approach the matter

most clearly by carefully defining "relevant issues" and then discuss how they come into play in

various "situations".

Once we all unambiguously know what we're talking about, we're much closer to achieving a civil conversation.

Relevant Issues

(in alphabetical order))

- Aesthetics

- When it comes down to it, many people simply do not like to see plants

growing outside of their natural range.

Aldrovanda vesiculosa

Example: If I am walking through a cactus forest in Arizona, I do not want to see an African daisy! (Regardless of how much affection I may have towards daisies.) Darling little African daisies are not what the cactus forests of Arizona are all about. I want to appreciate the cacti and their natural habitat for what they are in their original, unmodified beauty. (True example)

Example: Aldrovanda plants in a North American Utricularia pond are cheap adornments that detract from the beauty of a natural habitat. They occur there, not because of the splendor of the natural processes of the world, but rather only because some horticulturist put the plants there, just as if they had dropped a soda can. Biological pollution, they are. (True example) - Genetic Drift

- It is well known that there are variations within species. The Sarracenia

flava from Virginia are different from those of Georgia.

Indeed, populations of plants in neighboring bogs are often different!

If you introduce a plant to a new habitat, you are potentially disturbing

the natural gene pool of plants in that area.

Example: Suppose you sow seeds of Drosera capillaris with long leaves (from Florida) in a big South Carolina pond. These plants might interbreed with the native South Carolina Drosera capillaris. In time, the characteristics that make the South Carolina population unique may be lost. (Hypothetical example)

Example: You introduce Drosera capillaris with long leaves (from Florida) in a big South Carolina pond, and there aren't any other nearby populations of Drosera capillaris. Do you know how far a pollinating insect can travel? Do you know how far that bug can travel when the wind from a storm is blowing? It might be able to get to those surprisingly distant plants in the next county! (Hypothetical example) - Hybridization

-

Sarracenia leucophylla

Sarracenia rubra,

planted in New Jersey

A more extreme case of genetic drift, plants you introduce to a site could hybridize with other species, resulting in a hybrid swarm that could pollute the entire gene pool.

Example: Suppose you introduce S. minor to the New Jersey pine barrens (where it is not native), well within the range of naturally occuring S. purpurea. Pollinators visiting your plant may take pollen to native plants and produce hybrids. Never again could you observe an interesting S. purpurea in that area, without wondering if maybe it is just an artificial hybrid. (True example)

Example: Suppose you are a horticulturist in Texas, smack in the middle of S. alata habitat. Suppose you start growing other Sarracenia, and since the conditions are so nice, you grow them outside. You are within a bee's flight of native pitcher plants, and could easily damage the native Sarracenia genetics. (True example)

Example: Suppose you introduce S. purpurea from coastal Georgia to the Gulf Coast of Florida, secure in the knowledge that you have only moved a plant from one part of its native range to another (and you have only messed around with genetic drift issues). But then, shortly after, you read that biologists have decided that all the Gulf Coast S. purpurea are in fact a different species, S. rosea. Oops! (Hypothetical example)

Example: Think of the damage a single S. flava could do, in time, if transplanted to one of the few remaining populations of S. oreophila! (Hypothetical example) - Invasive Species

-

Utricularia inflata

invading Washington

The worst kind of organism you can introduce to the wild is a species which is considered "invasive". Invasive species are so good at pioneering new habitat and reproducing well that they are very difficult to control or remove. I cannot imagine that species of Sarracenia would ever be considered invasive---they take too long to mature and reproduce to be a problem. But this is not the true for all carnivorous plants.

Example: Drosera capensis and Utricularia subulata are introduced to a Californian Drosera rotundifolia site, and rapidly become impossible to remove because of the extent of the infestation. This site no longer is of interest to conservation organizations because of the biological pollution. (True example).

Example: Utricularia inflata is introduced far out of its range, to Washington state, probably by carnivorous plant horticulturists. It becomes an irritation to recreationists, and is likely to be declared as legally "noxious" and therefore illegal to grow in the state! (True example) - Legality

- You are not allowed to practice horticulture on land that you do not own. Regardless of whether land is owned by

a private person, company, conservation nonprofit, or government, in order to enter land and plant things there

you must be aware of the law in in full compliance with all regulations.

Example: You discover that a Venus flytrap in your collection was poached from public land. To make things right, you return to the public land with the plant in order to return it to the wild. You are apprehended by officials for poaching---the baggied plant in your backpack being used as prima facie evidence you were poaching. (Hypothetical case, but possible according to North Carolina law) - Pest Introduction

- Plants planted into the wild may carry greenhouse pests with them.

Drosera × hybrida,

planted in California

Example: You introduce a slow-growing, sterile hybrid plant (Drosera ×hybrida) into the wild. It is not invasive. However, you didn't realize that the soil ball with the plant contained invasive Utricularia subulata and soil pathogens (fungus) that could damage the environment. (Hypothetical case based on true example)

Example: I have observed that the populations of Darlingtonia artificially planted in Mendocino County, California, are heavily parasitized by what appears to be greenhouse thrips. I have not seen such damage on natural stands of Darlingtonia. Is it possible that these thrips might evolve to attack natural stands of Darlingtonia next? Perhaps they can already---arthropods are well known for their ability to evolve rapidly into new strains. In this case, it is fortunate no natural stands of Darlingtonia occur nearby. But if someone planted thrips-infested Sarracenia in a Darlingtonia bog, the thrips would find an easy foothold. Far from natural predators, the thrips could devastate the native carnivorous plants. - Science

- If you quietly introduce plants into the wild, you might confuse biologists and conservationists

who may expend a lot of energy on the plantings.

Dionaea muscipula,

planted in Florida

Example: The 1993 edition of the Flora of California (The Jepson Manual) lists D. linearis as occurring (artificially) in California. This is clearly an incorrect reference to plantings of D. capensis---some poor naturalist found the D. capensis plants and assumed they were wayward North American plants in California, instead of thinking about South African species! How many more people will now be confused by this erroneous report? (True example)

Example: Scientists are arguing about the native vs. non-native status of Venus flytraps in Florida, even though some horticulturists claim to know those who have done the introductions! (True example)

Example: Florida has a populations of native Drosera filiformis in western Florida. As these sites become endangered by development, companies seeking to destroy the sites could argue that these sites are probably only non-native plantings by horticulturists, and therefore not of conservation value. (Hypothetical example)

- Unintended Consequences

-

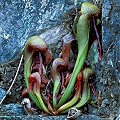

Darlingtonia californica

has been planted in Canada

This is an open-ended question that contains all the other dangers of species introduction. Do not introduce species carelessly---after habitat destruction, the largest cause of species extinctions is from introduced species (a statement from the top of this page that is worth repeating!). Many exotic species were introduced with high motives, but have caused huge biological catastrophes. Do not play God of Creation with the environment.

Example: It is simple reality that the plants you introduce must displace other plants. Perhaps a rare orchid will no longer have a foothold. Perhaps a delicate fern. Maybe even something as uninteresting as a species of grass. (Hypothetical examples)

Example: Perhaps a rare insect lives in the area---your carnivorous plant could be feasting at one of the insect's only habitats. (Hypothetical example)

Example: I know of a few carnivorous plant bogs which are not of interest to conservation organizations because enthusiasts have planted carnivorous plants there---the conservation organizations consider the sites "artificial" and not worthy of protecting as representatives of natural areas. (True example)

Situations

1)When plantings are being done outside a plant's natural range...

Aesthetics: An issue for those who don't like your meddlings.

Hybridization: An issue.

Invasive species introduction: A very important consideration.

Legality: I'd be worried about this, if I were you.

Pest introduction: A very important consideration.

Science: Important.

Unintended consequences: This should keep you up at night.

2)Plantings within a plant's natural range...

Aesthetics: Make sure this isn't an issue in your case.

Genetic drift: This is important.

Legality: I'd be worried about this, if I were you.

Pest introduction: A very important consideration.

Science: Important.

Unintended consequences: This should keep you up at night.

As long as all the issues have been properly analyzed by yourself and other experts (not just your buddies),

the project should be be done as part of a successful habitat restoration plan that is being carefully monitored.

3)As a form of conservation...

Even if the plant you want to introduce to the wild is an endangered

plant with a limited range, you must still consider all of the

relevant issues I describe below. You must behave responsibly.

It is difficult to justify introducing a plant into the wild (but

outside its normal range)

if it growing successfully in cultivation---the wildland planting is

just as artificial as a plant in a greenhouse.

Noting this, the planting of common plants like Drosera capensis or

Utricularia subulata in the wild is unjustifiable. The fact

they are invasive species makes planting them indefensible!

Page citations: Hickman, J. 1993; Randall, J.M., and Marinelli,

J. 1996; Rice, B.A. 2002, 2006a; personal observations.